Welcome back to the series where I try to cover what we’ve been doing wrong by having activities and fragments as views in android development. If you haven’t read the first part, I’d encourage you to so that we’re on the same page. Click here for part 1.

We’ve talked a bit about what activities are in the android platform, but we didn’t cover exactly what it means to deal with it as a view. I believe it’s somewhat clear to most that I’m talking about the set of classes in MVC-like patterns that are responsible for basically wiring a layout with data and interaction listeners. How we shape the data we’re wiring depends on how we decided to shape our model, and how the view receives said data depends on who is our controller, but the view only displays it, whether it’s a loading state or your bank account balance.

How we “fill-in” the data provided by the controller in the view depends on the tooling we have at hand. In android we could go the classic route of balance_text.setText(formattedBalance), go full data binding with android:text="@{balanceViewModel.formattedText}", or do whatever a third-party library (or “third-first party?” like the upcoming Compose) allows us to.

How we read user interactions is also very tooling dependent. In android, the good old way to capture one of the basic user interactions, a simple click, is to give an element an OnClickListener. The view should not decide what to do when there’s a click on a button, it should only notify whoever controls it that that button has been clicked, and then the controller should decide what to do. How it’s notified depends on what kind of controller you have as well. See that by controller, in this context, I’m referring to MVC controllers, MVP presenters, MVVM ViewModels, etc.

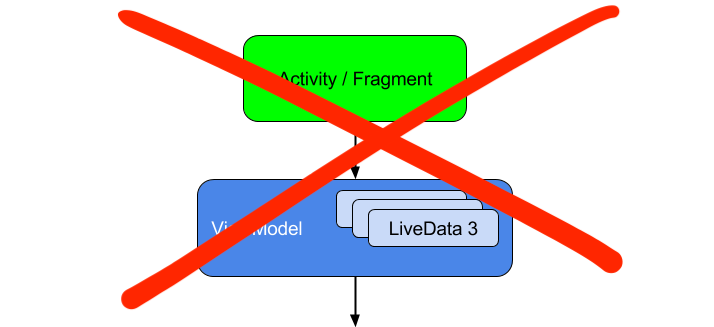

I honestly believe pretty much any of the MVC alternatives may work effectively in android as long as proper responsibility boundaries are placed and classes can effectively fulfill what they’re expected to. I like the dynamics of unidirectional data flow, that allows a view for a very interesting way of communicating with its controller, and I also do believe MVP is still very effective for most scenarios. Even MVVM could be a choice, but keep in mind I’m talking about the pattern, not the AAC libraries. MVVM stems from much earlier than Jetpack, in fact for at least over a year before it was announced on 2017 Google I/O. I won’t go into details of these specific patterns here. This droidcon talk by Zukanov, the same author of the 2015 article, mentions some of these ideas.

The core idea is to narrow down what the view does as much as possible because what we’re aiming for with these design patterns is to isolate view from logic. Picture a view as a lazy foreigner douchebag that speaks in a weird language. It only does what it wants to, in a way that may be strange to you. It only does things he learned wherever he comes from. The language is difficult and if one tries to speak “too much” it’s easy to accidentally get him pissed, and you don’t want to see him pissed, so it’s better to communicate only what’s essential whenever you need to make a point. That’s more-or-less how we should deal with views.

what it looks like to use an activity as a view

Are we crossing the line of “too much talking” when dealing with activities as views? Well, let us see a simple example

private const val PROFILE_SUCCESS_REQUEST_CODE = 123

private const val HOME_STATE_REGISTRY = "home_state"

class HomeActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

@Inject

lateinit var controller: HomeController

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

AndroidInjectors.inject(this)

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.home_activity)

controller.state.observe(this, Observer { state ->

updateState(state)

})

savedInstanceState?.let { state ->

controller.restoreState(state)

} ?: run { controller.fetchData() }

listenInteractions()

}

override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle) {

outState.putParcelable(

HOME_STATE_REGISTRY,

controller.state.value

)

super.onSaveInstanceState(outState)

}

override fun onActivityResult(

requestCode: Int,

resultCode: Int,

data: Intent?

) {

if (requestCode == PROFILE_SUCCESS_REQUEST_CODE &&

resultCode == RESULT_OK

) {

controller.fetchData()

}

}

private fun listenInteractions() {

buttonTransfer.setOnClickListener {

goTo<TransferActivity>()

}

buttonPayBill.setOnClickListener {

goTo<PayBillActivity>()

}

buttonUpdateProfile.setOnClickListener {

goTo<UpdateProfileActivity>(

forResult = true,

requestCode = PROFILE_SUCCESS_REQUEST_CODE

)

}

buttonRefreshData.setOnClickListener {

controller.fetchData()

}

}

private fun updateState(state: HomeState) {

loadingIndicator.isVisible = state.isLoading

groupUserData.isVisible = !state.isLoading

textUserName.text = state.userName

textAccountNumber = state.accountNumber

textBalance = state.formattedBalance

}

private inline fun <reified A : Activity> goTo(

forResult: Boolean = false,

requestCode: Int = 0

) {

val intent = Intent(this, A::class.java)

if (forResult) {

startActivityForResult(intent, requestCode)

} else {

startActivity(intent)

}

}

}

With a HomeController that looks something like this

class HomeController(

private val fetchUserDataUseCase: FetchUserDataUseCase,

) {

private val _state = MutableLiveData<HomeState>()

val state: LiveData<HomeState> get() = _state

fun restoreState(savedState: HomeState) {

_state.value = savedState

}

fun fetchData() {

_state.value = HomeState(isLoading = true)

coroutineScope.launch {

val response = fetchUserDataUseCase

.execute()

val formattedBalance = getString(

R.string.balance_format,

esponse.balance

)

_state.value = HomeState(

isLoading = false,

userName = response.user.name,

accountNumber = response.account.number,

formattedBalance = formattedBalance

)

}

}

}

This example shows what a regular activity usually does. It inflates the views with data as it’s supposed it. It also listens to user interactions. However, notice it also takes the reins of responsibilities it should not.

- It is aware of the lifecycle events of the system. Not only it deals with an

onCreate()event, which could be fine, it also needs to know it may have to restore state at that point, which now means it may know a little too much. - It needs to handle data integrity, here in the form of its state. The system mechanism for saving instance state is the only reliable tool for the job. It could be abstracted out through fancy engineering like what’s been done with ViewModel AAC, but I’d say it’s beyond the point of trying too hard.

- It handles navigation. Navigating through activities can only be done by the system, and the way to notify it to do that is by sending an

IntentthroughContext.startActivity()(that’s required to be from a task with at least one runningActivity). Again, offloading that to the controller requires fancy engineering. Not only the “going to” is handled, but the return from a specific screen is also listened to decide on whether or not to refresh data. - A good part of the decision-making process of system events (it shouldn’t be aware of) and user interactions is made here. That happens because it makes no sense to offload these decisions to the controller within the constraints we’re facing. Why would anyone notify the controller that the user wants to navigate to a new screen if the controller will need to ask back the view to navigate anyway? The decision on whether to use data from the saved state or another source is entirely made by the view!

The view alone makes the most of the weight-lifting, with the controller being but a shy helper. That’s not very far from how we would do it with AAC ViewModels, is it? Let’s not forget, this is a very simple example of a view. One that fits a demo app, but too simplistic for most production codebases which compose of multiple different elements displayed at once, like bottom navigations, menus, carousels, etc. In this limited scenario, we were already able to pinpoint multiple design flaws. We’re definitely talking too much here.

BONUS! And what about fragments? Would they serve us here? To find that out is actually quite simple, picture the same scenario we have here, with the same controller interface, using Jetpack Navigation. Did the code change effectively? Does it look quite like the same? I won’t go as far as to rewrite it within a Fragment, but I know for a fact the design would be pretty similar, with changes that stem from the fact that platform specifics have leaked to the view way too much. Fragments as views are still bad.

so what do we do with activities, really

As I’ve already mentioned in the previous part of this series, activities are entry points to your application. That’s how the Android system sees it. That’s why it needs to be managed by the system. Therefore, it should be pretty basic to understand why it simply makes no much sense to have any kind of 1:1 relationship between an activity and a view, regardless of whether it’s an element or a screen.

That being said, I should add that constraining views to the idea of “screens” is something I believe to be limiting. Of course, that’s a valid way to organize your application, but the idea of modeling your views independently on how they’ll fit in the outside context unlocks new possibilities. Being able to compose different views within a single context sounds like a great power to have, and one of the things I look forward to seeing if the upcoming Compose library (hence its name) will be able to achieve seamlessly. This 2019 summit speech brilliantly raises a lot of points about UI and UX in android development.

Probably, the way to achieve the closest to an ideal scenario would be to avoid using platform classes to represent any of the classes in an MVC scenario, as radical as it may sound. That would require a lot of tooling to be built, and that’s not an easy task. Thankfully, there are several already functioning options for things like navigation and dependency inversion out there. Uber seems to have succeeded with implementing the tooling for their RIBs architecture, check for yourself if that’s the kind of challenge you’re up to take (I confess I didn’t study it enough to see how it works). Square also built their own stack. There are less complex options on the table as well. All of that in mind, the answer to what is the best approach depends on each developer and team’s specific needs.

I can’t recommend building the whole stack to anyone. Whoever wants to do it anyway has enough reason to, and doesn’t need a recommendation. As long as one is sure to know what they’re doing, it should work. What I recommend if you want to take a simple approach is use fragments instead of activities, but use them as controllers, not views. It may or may not be the best approach for many scenarios including yours, but one thing I can safely say is that it’s better than using either activities or fragments as views.

Let’s move our previous example from activity view to fragment controller, with a separate view class, for now without extra tooling (bear with me for a moment, I know this first iteration still looks icky, but that’s just a sneak peek of how it would look like to have the fragment as a view).

private const val PROFILE_SUCCESS_REQUEST_CODE = 123

private const val HOME_STATE_REGISTRY = "home_state"

// We can leverage FragmentFactory for constructor

// injection, making android injection not required

class HomeController(

private val fetchUserDataUseCase: FetchUserDataUseCase,

private val navRegistry: NavigationRegistry

) : Fragment(R.layout.home_activity) {

private lateinit var view: HomeView

private lateinit var state: HomeState

set(value) {

view.updateState(value)

field = value

}

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Necessary for reliably reading

// saved instance state

retainInstance = false

}

override fun onViewCreated(

view: View,

savedInstanceState: Bundle?

) {

this.view = HomeView(this, view)

}

// More reliably read savedInstanceState

override fun onActivityCreated(

savedInstanceState: Bundle?

) {

super.onActivityCreated(savedInstanceState)

val registry = savedInstanceState

?.get(HOME_STATE_REGISTRY) as? HomeState

if (registry != null) {

state = registry

} else {

fetchData()

}

}

override fun onDestroy() {

super.onDestroy()

coroutineScope.cancel()

}

override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle) {

outState.putParcelable(HOME_STATE_REGISTRY, state)

super.onSaveInstanceState(outState)

}

override fun onResume() {

super.onResume()

val result = navRegistry.findResultFor(

navRegistry.UPDATE_PROFILE

)

if (result == navRegistry.RESULT_OK) {

fetchData()

}

}

fun fetchData() {

state = HomeState(isLoading = true)

coroutineScope.launch {

val response = fetchUserDataUseCase

.execute()

val formattedBalance = getString(

R.string.balance_format,

response.balance

)

state = HomeState(

isLoading = false,

userName = response.user.name,

accountNumber = response.account.number,

formattedBalance = formattedBalance

)

}

}

fun transfer() {

goTo(navRegistry.TRANSFER)

}

fun payBill() {

goTo(navRegistry.PAY_BILL)

}

fun updateProfile() {

goTo(navRegistry.UPDATE_PROFILE)

}

private fun goTo(

destination: NavigationRegistry.Destination,

navOptions: NavOptions = NavigationRegistry.defaults()

) {

findNavController().navigate(

destination.key,

navOptions

)

}

}

While our view looks as follows:

class HomeView(

private val controller: HomeController,

private val view: View

) {

init {

with(view) {

buttonTransfer.setOnClickListener { controller.transfer() }

buttonPayBill.setOnClickListener { controller.payBill() }

buttonUpdateProfile.setOnClickListener { controller.updateProfile() }

buttonRefreshData.setOnClickListener { controller.fetchData() }

}

}

fun updateState(state: HomeState) {

with(view) {

loadingIndicator.isVisible = state.isLoading

groupUserData.isVisible = !state.isLoading

textUserName.text = state.userName

textAccountNumber = state.accountNumber

textBalance = state.formattedBalance

}

}

}

Our view finally looks like what it should look like, but would you look at that controller… The thing is, a lot of what it is doing isn’t much related to the Home screen logic. There’s a bunch of steps just to conform to how the system works. That’s where we can leverage some tooling, just a little bit, see

private const val STATE_REGISTRY = "state_registry"

abstract class Controller<State : Parcelable> : Fragment() {

abstract val view: View<State>

private var state: State? = null

set(value) {

if (value != null) {

field = value

view.updateState(value)

}

}

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Necessary for reliably reading

// saved instance state

retainInstance = false

}

abstract fun initState(): State

// Ignore savedinstancestate here

override fun onCreateView(

inflater: LayoutInflater,

container: ViewGroup?,

savedInstanceState: Bundle?

): android.view.View? {

return view.inflate(inflater, container)

}

override fun onActivityCreated(

savedInstanceState: Bundle?

) {

super.onActivityCreated(savedInstanceState)

val registry = savedInstanceState

?.getParcelable<State>(STATE_REGISTRY)

state = registry ?: initState()

}

override fun onDestroy() {

super.onDestroy()

coroutineScope.cancel()

}

override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle) {

if (state != null) {

outState.putParcelable(STATE_REGISTRY, state)

}

super.onSaveInstanceState(outState)

}

protected fun setState(setter: (State) -> State) {

state = setter(state ?: initState())

}

// This would be better placed in an outside

// dependency, or an extension function if you will

// but I'll keep it here for simplicity

protected fun goTo(

destination: NavigationRegistry.Destination,

navOptions: NavOptions = NavigationRegistry.defaults()

) {

findNavController().navigate(

destination.key,

navOptions

)

}

}

Pair that with a generic contract for views

interface View<State : Parcelable> {

fun inflate(inflater: LayoutInflater, root: ViewGroup?): View

fun start()

fun updateState(state: State)

}

That removes boilerplate to handle some of the platform specifics and sets some of the responsibilities which a controller is expected to take. We also add some abstraction between the controller and view. With that we’re able to rewrite the controller like this:

class HomeController(

private val fetchUserDataUseCase: FetchUserDataUseCase,

private val navRegistry: NavigationRegistry,

viewProvider: (HomeController) -> View<HomeState> = { HomeView(it) }

) : Controller<HomeState>() {

override val view: View<HomeState> = viewProvider(this)

override fun initState() = HomeState(isLoading = true).also {

fetchData()

}

override fun onResume() {

super.onResume()

// Don't refresh on every on resume, just when

// we come back from an updating action

val result = navRegistry.findResultFor(

navRegistry.UPDATE_PROFILE

)

if (result == navRegistry.RESULT_OK) {

fetchData()

}

}

fun fetchData() {

setState { HomeState(isLoading = true) }

coroutineScope.launch {

val response = fetchUserDataUseCase

.execute()

val formattedBalance = getString(

R.string.balance_format,

response.balance

)

setState {

HomeState(

isLoading = false,

userName = response.user.name,

accountNumber = response.account.number,

formattedBalance = formattedBalance

)

}

}

}

fun transfer() {

goTo(navRegistry.TRANSFER)

}

fun payBill() {

goTo(navRegistry.PAY_BILL)

}

fun updateProfile() {

goTo(navRegistry.UPDATE_PROFILE)

}

}

And we finally end up with something that looks like what a controller should. We could use a mapper so that we get a correctly constructed HomeState instead of whatever val response holds, and it would look even slimmer. Notice how there are a few advantages we have here:

- We’re calling

onResume()because we care about that possible side effect. We might have to refresh the data. That’s logic we’re handling in the controller. - We have easy access to resources without the need for complicated trickery, which allows us to hand the view strings that are ready to be displayed, as seen with

formattedBalance. - The view has no idea of what it means to navigate, it only tells the controller that’s what the user intends to do.

- No sorcery needed to effectively save and restore the state.

- We can leverage existing tooling of the platform so we don’t need to bother with it ourselves.

- Decouples your presentation logic from external dependencies that don’t take your project’s needs into perspective, which might make it a starting point for larger-scale apps to define their tooling.

You might be wondering how it is to test this. Since it’s a fragment, don’t we need to run it within an instrumented environment to run tests? Well, we actually don’t! Simply instantiate it like any class and it just works. And better yet, we’re able to fluently test aspects like resuming to the screen.

@Test

fun doesNotUpdateOnResume() {

val subject = HomeController(

testFetchDataUseCase,

fakeNavRegistry,

{ mockView }

)

subject.onResume() // Calling lifecycle callback from local tests

verify(exactly = 0) { mockView.updateState(any()) }

}

Sure, we also need to make our view comply to the interface, but that’s not complicated at all, as we can see.

class HomeView(

private val controller: HomeController

) : View<HomeState> {

private lateinit var view: android.view.View

override fun inflate(inflater: LayoutInflater, root: ViewGroup?) =

inflater.inflate(R.layout.home_view, root, false).also { view = it }

override fun start() {

with(view) {

buttonTransfer.setOnClickListener { controller.transfer() }

buttonPayBill.setOnClickListener { controller.payBill() }

buttonUpdateProfile.setOnClickListener { controller.updateProfile() }

buttonRefreshData.setOnClickListener { controller.fetchData() }

}

}

override fun updateState(state: HomeState) {

with(view) {

loadingIndicator.isVisible = state.isLoading

groupUserData.isVisible = !state.isLoading

textUserName.text = state.userName

textAccountNumber = state.accountNumber

textBalance = state.formattedBalance

}

}

}

That does come with an added cost of abstraction, but preserves flexibility and makes creating new controllers a lot easier than it would otherwise seem. Also notice how an abstract class for View<State> could take the layout id and implement inflate() for us to never bother about that as well. The shown approach gives us room to choose the implementation approach, we could also have an abstract class that would work with the new view binding. In fact, that’s exactly what I’ve done in one of my projects. If you’re still not convinced this is a better outcome, roll the page back up and see how our HomeController and HomeView compare to our original HomeActivity().

It’s very important to say that this is an example that, while it will work in a lot of scenarios, it may not be sufficient in some. I have been using it in personal projects but have yet to use something like that in more complex requirements, and have been testing with other ideas. I would say the closest to ideal would be to isolate the platform altogether, but let’s not complicate things too much here.

controller meets context

It has long been commonplace to isolate the Context, the core of the system APIs we have access to. The general idea, however, was to isolate it inside the view by placing its logic in the Activity/Fragment. That’s part of the reason why we had to rely on the view to deal with things that are side effect to it, like navigation or requesting string formats and other resources. As it’s already been said, that’s a bad idea, it makes little sense. Effectively, we’re leaking system APIs into our view classes, which is contrary to what we’ve been discussing.

We still may need to access some of these APIs somehow, and the best way is to have the controller doing this job, of course! It becomes capable of handling these things on its own, which is closer to how it should be. In short, the controller should never depend on the view to handle these kinds of side effects.

Let’s visualize three different elements in this relationship, the view, the logic, and the platform.

The logic is the cornerstone of the presentation, and it should only change if requirements change. The platform is the part of the framework through which we communicate with system APIs and general possible side effects that aren’t directly related to user interaction. The view is the structure that dictates what the user sees/hears. It offers ways through which the logic can handle its data and direct user interactions.

It hardly makes any sense that logic depends on view to communicate with platform. It is logic that needs to be the one to establish the interactions of platform and view. There’s a little bit of clean architecture here if you pay close attention. All of that said, it’s not yet ideal to have your controller being itself an instance of Context, or being necessarily tied to it. That indicates a tight coupling of logic and platform, but it is a big step forward from having the view being an instance of Context.

wrapping up

Congratulations on coming this far. I admit it’s been a long ride, We’ve discussed a lot of things here.

- What Activities are in the Android platform.

- Some of the philosophies behind MVC and patterns alike.

- How we can’t effectively separate view from external side effects by using activities (or fragments) as views.

- How fragments as controllers is a twist that can help us achieve a more reasonable design.

- An alternative design built upon the idea of fragments as controllers.

- That there’s still room for improvement.

Bear in mind that the key point here is not to advocate for fragments as controllers, but rather to advocate that we should stop adhering to designs built upon activities/fragments as views. When Jetpack Compose finally arrives, I hope it becomes very clear how proper separation of view and logic is better attainable without relying on platform classes as if they were views. That, however, depends on the path that Google will take while creating the tooling for Compose, which is yet unclear by the time of writing this.

Whether you want to rely on the basic tooling of the framework, on solutions built on libraries like Jetpack Navigation, on your own stack of tooling, or some other third party like Uber RIBs, the one message I have to bring is simply don’t use activities or fragments as views.