Mobile platforms like Android and iOS changed the way we use technology almost entirely. The world moved from a landscape dominated by desktop applications to one that sees a yet increasing amount of mobile applications and ideas year after year.

It’s been over a decade since both Apple’s and Google’s systems wiped the mobile market with a new face, however it seems like we’re still getting used to what these platforms allow us to do. One of the big indicators I see that make me believe that is how it’s still common ground in Android development to deal with activities as if they were views. By views we’re talking about the holders of UI logic in an MV-something design.

– Is it wrong to have activities as views in my app?

The short answer would be yes. It works but is far from ideal. It’s been long since the idea of “God Activities” was ditched, but we’ve moved to a path where solutions seem to have this one thing in common: Activities (or Fragments) are the holders of view logic. The idea that this might not be ideal isn’t anything new. Uber moved on from it in favor of its own RIBs architecture. Square, famous for libraries like Retrofit, iterated through ideas like mortar and currently supports workflow. It’s something that has been subject of concern for at least since 2015. There are many philosophical and practical reasons these engineers spotted that lead them to move away from this standard.

I’ll also give a longer and more defined answer, and for that matter, I will cover two important aspects to consider: How Android works as a platform for third-party software (that we create, in this part) and the philosophy of presentation design patterns (that we use, in the next part). In the last part, we’ll also review how to have a working sample of this idea with little effort and with little dependency on external libraries, like Lifecycle AAC.

the android platform

A new kind of user experience is what lead people towards the world of “smartphones”. Being able to quickly perform tasks that would otherwise be anywhere between “mildly less convenient” and “painfully tiresome” without these new gadgets has been massively appreciated by people from largely different backgrounds. “Ubiquity” in software now covers a range where the terminology is much closer to be indeed accurate and not just a business jargon.

With all of that in perspective, building a platform that would allow for this massive integration of different tasks and ideas wouldn’t come without some change and challenge. Reshaping the way users interact with software would have to be part of the deal, and it was.

Before the realm of modern mobile platforms, there were several different systems from multiple OEMs around the world. Creating software for them was anything but a streamlined experience (is it the case nowadays?). One thing about all of those I can remember is they shared somewhat of a “closed box” philosophy. That means designing applications as isolated from the outside world as possible, communicating with necessary external resources through some kind of intermediary layer the software would be built on top of. Not that proper isolation was ever an easy goal, but we tried.

Even though developers depend on the system for things like drawing it’s UI or reach for other I/O resources, the general design of the application would be constructed within a closed box not to taint its domain with specifics of the platform. That idea wasn’t original to these systems, that’s pretty much how applications like desktop ones have always been designed. This complicates matters a little when we wish to establish communication with other applications. That kind of system integration contributed to the fast obsoletion of those systems in face of android and iOS. These modern platforms had the setting of new kinds of channels between applications as one of their goals.

First and foremost, it is a generally good practice to effectively abstract out system definitions as much as possible, so that your design can make use of freedom of choices as to how you want things to work. As I said, you don’t wish to taint your domain with the specifics of the platform. What kind of leads us to question why would we use the most system-impregnated class we’ve got access to, the Activity class, as a view. Anyway, the difference in android is that the overall design of what an app does needs to take into consideration what the system expects from it, and it expects more than a closed box. Instead, it expects an open box of resources that can be useful. You may say it to be an open box of smaller closed boxes.

What are these resources? You probably know all of them, or at least already heard of them.

- Content Providers, or just providers.

- Broadcast Receivers, or just receivers.

- Services

- Activities, of course

Each of these resources exists for a specific purpose. Services exist so that we can offload work from the UI, which allows us to keep things running while the user does other stuff (except since API 24 we’re required to keep these services on the foreground, usually through system notifications). An example of background service is the Firebase messaging service. Pretty much any application has its own instance of this service since that’s what allows them to receive push notifications.

I won’t extend too much on content providers and broadcast receivers, but they are simply more ways through which our application allows the system to communicate to it. Either by telling the system it wants to listen to specific broadcast channels or telling that it provides access to data that it manages.

now activities

And then we have activities. It’s very important to understand what they are within the context of the android platform. The name itself sounds like it doesn’t say much, especially when we’re taught to use them to represent “screens” in beginner courses around there. The name sounds off, but it makes some sense through this angle.

Of the many things the system designers expected from app developers, it makes obvious sense to have a custom UI that enabled the user to do what that app promises to. Of course, there would be a way to control the system window to present a UI that allows the user to perform a task. Said tasks could be split into multiple activities or a single one. Thinking about it this way, the naming now sounds a little plausible, but still feels like playing some semantical gymnastics. There could’ve been a better name, perhaps.

That leads to how the system expects to handle the UI part of its applications, through tasks which can be composed of one or more activities. However, these are not things provided by applications, but rather spawned by the system once it’s desired to run an app. Tasks do depend that the user interacts with applications for the system to create them, but from that point onwards it’s not tied to only that app, it can expand its context to other apps as well and communicate with them with little friction. That allows for an entirely new way of integrating two completely separate pieces of software, managing to power the user to perform tasks very efficiently.

Your parents can send you an IM with your aunt’s new phone number and you can easily add them to your contacts list by clicking the number, that brings you directly to the “new contact” screen of your phone app. Your friend can send you a picture with a bill for the money you borrowed and by clicking it you’re brought directly to the “pay bill” part of your bank app. Things are faster, easier, and as seamless as never before. That is the power of a more “open” software design when it comes to mobile platforms.

That’s the kind of resource android expects the developers to bring within their applications, different entry points for UI interactions that represent different activities in their application so that the user can make use of them, either through the icon in the menu that leads to the launcher activity, or by stating that it’s accessible through a specific URI, or media of certain MIME type, and a variety of other ways to declare it. There’s very little reason in specifying more activities if they don’t serve as alternative entry points to your application, it’ll only add overhead to the system and bloat your AndroidManifest.xml.

A good analogy I’ve seen around is that having multiple activities for your app is somewhat like having multiple “.exe” files in your app for every different screen. Of course, that’s not meant to be an accurate description, but it helps us visualize how the Android system sees activities.

what lead to an activity-driven design

There are several challenges when it comes to setting up a software design that properly contemplates the needs of UI/UX decisions in any application. There’s the need of having a way to change the contents of the window and bring the user to another view, often keeping the context of where he was in the previous one. Things can’t “go boom boom” if the user decides to change screen orientation. Sometimes it’s desired to keep data if the user moves to another task momentarily, it may also be desired to refresh the information. The needs are many and the tooling needs to contemplate them.

Tasks are very powerful. They can hold data that of each activity it has in its stack and if it is killed by the system for whatever reason, like lack of available memory, it manages to keep that data. Oh, and by the way, it has a stack, the Activity Backstack, which solves many of the mentioned situations. A task can pile activities one upon another and unpile at need, allowing the user to move to a new one without losing the context at which he left the previous one. That also allows the task to communicate to them that they’re being terminated by the system and asks them about extra data to save through Activity.onSaveInstanceState(), which solves even more problems.

Activities also have lifecycle callbacks that make them aware of different events that they’re going through. That allows them to decide whether or not to refresh data upon resuming through Activity.onResume(), for example. For what it looks like, there’s sufficient tooling for a working UI within their API.

The apparent lack of sufficiently appropriate tooling that would allow these and other responsibilities to be offloaded from activities left beginners (and also people creating content for beginners) in a hard place when it came to alternative ways of designing their first application. The process of managing all of these scenarios can become quite difficult if we decide to do everything from the ground up. Fragments weren’t so much of an alternative before jetpack Navigation, since manually managing transactions and the stack is a challenge on its own. (Fragments aren’t very good candidates for views either, but the reasons will become more apparent in the next installment of this series)

Ultimately, having multiple activities to represent multiple screens became very commonplace in android development because even though many of the downsides were pretty obvious, it was a convenient way of doing so with the tooling at hand. And what are these obvious downsides, you may ask?

why should that change

I’ll only mention part of the practical reasons in this part. In the next part, where I go more in-depth about views, we will explore another set of problems with activities (and fragments) working as views

The first problem is the number of things we need to manage within a single class. Long are the days of God Activities, but there’s just so much responsibility left in the back of these classes that there’s still reason to think they represent some divine being in many codebases. Wire the layout with the data and listeners it needs, manage the lifecycle, control navigation, and even still handle data lifetime. Add to the mix eventual permission requests and even requesting external resources from the system like other activities. That’s a lot of stuff for a single class. There’s very little domain isolation!

What differs this from the God Activities of olden days is that all sorts of I/O operations like reading files, writing to the database, and sending network requests were also in the middle of the mix. That isn’t half of what the Activity class did. Since only part of it was offloaded, is it wrong to believe it’s but mere steps down the deity hierarchy?

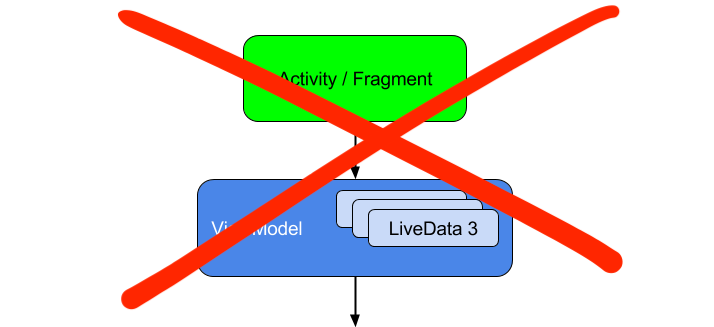

There’s the attempt to offload one of these responsibilities from activities through the means of ViewModel, part of Lifecycle AAC. It is meant to be responsible for taking care of the data that view needs. It even has the means to listen to lifecycle events so that the activity wouldn’t have to bother about kickstarting things on its own. However, that was only achieved with activity as the view through a lot of sorcery with factories, providers, stores, and saved state handlers. I do admire that they managed to make it work with an API that is not so complicated to use, but boy is it complicated to understand.

And what about navigating through screens? It’s enabled by default for activities through the aforementioned Activity Backstack. But it’s pretty bad. Well actually, it’s not bad at all, it works perfectly for what it was designed for, which is allowing activities of any app to communicate in a single stack. It’s not meant for much more than that, however. Try to create the navigation for a purchase flow. You may end up with something like ShoppingCartActivity -> PurchaseActivity -> PaymentMethodActivity -> PurchaseAcceptedActivity. Once the user is done with it, what’s desired is to bring him back to whatever screen they were before ShoppingCartActivity. Achieving that with the Activity Backstack is egregious, that’s not what it’s there for! Now imagine having bottom navigation desired to keep multiple stacks. You’re out of luck.

To mitigate the navigation problem, Google themselves introduced more specialized tooling that better suits the needs of most common navigation challenges out in the wild, like the one of the shopping app. Jetpack Navigation handed developers a much more capable suite for application UX desires, but that came with the cost that it couldn’t work with activities. And how could it, since they are managed by the system after all? We can’t write code that manages Activity instances, therefore it was necessary to use something else.

Fragments were chosen for that matter. Lo and behold, jetpack ViewModels also serve fragments. We’ve reached sufficient tooling to move from activities to fragments, for what it seems. Well, at least Google believes that since it has been promoting single-Activity as standard for Android Development ever since.

While activities are the system provided entry points into your app’s UI, their inflexibility when it comes to sharing data between each other and transitions has made them a less than ideal architecture for constructing your in-app navigation. Today we are introducing the Navigation component as a framework for structuring your in-app UI, with a focus on making a single-Activity app the preferred architecture.

Looks like Google agrees with much of what I’ve already mentioned about activities, even the entry point part. Still, the alternative is suboptimal. Fragments share many of the details that keep an Activity from being an effective candidate for a view, which I cover in the next part. So for now take Google’s word for that, not mine. I hope to see you in the next installment of this series.

Part 2 is already available here.