Android development is very much a thing of its own. A screen is not a Screen, but an Activity. Or even a Fragment. Your software engineering convictions are put to test in this environment where you have to shape your code to what the SDK is able to offer. We’ve come a long way, and things have evolved a lot. We’ve been presented with many new APIs since the release of Pie (API 28), that range from better accessibility tools to aid building proper accessible navigation like the XML tag isHeading and it’s programatic backwards compatible version, to finally being able to properly set the color of your shadows without having to manually create drawables out of thin air. And the brand new AndroidX with it’s many mysteries (and plenty of other stuff).

But alas, old problems are old problems and they’re still there, we just deal with them with a different approach. How do I keep state through configuration changes? How do I keep the button that calls another activity from calling multiple activities through repetitive clicks? When is it time for an update of our view data? There’s not the case of a “one to rule ‘em all” answer here. But lets take a step at a time.

Let’s start with something simple, a single screen, a number and a button that increments the number. I will assume that you’re familiar with android development from now on.

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity(R.layout.activity_main) {

private var count: Int = 0

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

textView.text = "$count"

button.setOnClickListener {

count++

textView.text = "$count"

}

}

}

Easy as it looks, the unadvised would believe that this is good enough. You and I, though, know it’s not. The reason? Activity instances don’t live exactly like one would expect. Not only can it go through a whole new lifecycle event once we change from portrait to landscape mode, the original instance dies and a brand new one is created. This means our count instance goes back to zero every time. No news here. You might be wondering, however, what that ComponentActivity there is. It’s part of the AndroidX Activity component. I won’t go into details about it here, but one thing we can do is pass the layout reference to the super constructor instead of calling setContentView(), as long as we keep exposing a default constructor in our concrete class.

There are a few things we could do in order to keep that information alive if we want to. That savedInstanceState parameter could keep the count value for us. That’s the way it’s always been done. We only need to override the method that saves the bundle, and read it upon creation.

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity(R.layout.activity_main) {

private var count: Int = 0

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

savedInstanceState?.let { state ->

count = state.getInt("COUNT", 0)

}

textView.text = "$count"

button.setOnClickListener {

count++

textView.text = "$count"

}

}

override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle) {

outState.putInt("COUNT", count)

super.onSaveInstanceState(outState)

}

}

This sorts things out for us. But it requires us to parcelize or serialize any object that is not originally supported by the Bundle class. That somewhat hinders typesafety. We also need to do the saving and restoring of the value manually. A ViewModel isn’t news for an android developer by now. It kind of resembles a presenter, with the exception that it doesn’t know who reads the data it exposes. I’d say it’s a presenter that implements observable pattern. Through some magic, AAC ViewModels have means to keep state. Let’s have a look.

class MainViewModel {

var count = 0

fun inc() {

count++

}

}

No backing properties, lifecycle awareness or whatever for now. Lets look at this API. It simply exposes the data and an action we can perform with it. It all looks simple and tidy, and now we can replace the references to count in the first version of our MainActivity to a reference to the ViewModel, like that:

val viewModel = MainViewModel()

...

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

button.setOnClickListener {

viewModel.inc()

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

}

Problem is, the state of count can only survive as long as the ViewModel instance is kept alive. We basically came back to square one, because it won’t be kept alive through configuration changes nor process death. Our new class alone is powerless against the tides of android lifecycle and requires something else. In fact, our new code, as it is, is nothing but a hardly necessary wrapper to count itself.

What makes a ViewModel a powerful tool for keeping state is the fact that it is a class separated from the activity that can be kept alive independently from lifecycle, whereas the activity can’t. However, something needs to do this job. We could delegate that to the composition root of our application, if we could add objects to it. We could use a Dependency Injection framework, attach something to the application context, there are many options now. One of them would be a static provider.

Keep in mint that all of what’s discussed here serves solely configuration changes. By the time this text was written, saved state handles had not yet been released, and ViewModels’ data could not survive process death. So the remainder of this text will focus more on the event of configuration changes.

object GenericProvider {

val store: MutableList<Store<*>> = mutableListOf()

data class Store<T : Any>(

val clazz: KClass<T>,

val value: T

)

inline fun <reified T : Any> provide(factory: () -> T): T = store

.find { it.clazz == T::class }

?.let { it.value as T } ?: factory()

.also { store.add(Store(T::class, it)) }

}

Now we can wire it up with our activity

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity(R.layout.activity_main) {

private val viewModel = GenericProvider.provide { MainViewModel() }

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

button.setOnClickListener {

viewModel.inc()

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

}

}

}

And we’ve finally made our ViewModel effective in holding our state through configuration changes. It wasn’t without a significant amount of work, and it’s not even properly polished.

On a higher degree of an application we could make it so that the ViewModel could die as we exited the scope of a screen and we wouldn’t be wasting memory. Whatever MainViewModel holds will survive through the entirety of the application, and we could be allocating a lot of unnecessary space as soon as the app starts scaling. The lookup isn’t the most efficient either. Process death would nulify static references and could cause unexpected NPEs. Nevertheless, we understood something valid here, how ViewModels are able to hold our states, which is by being held by something else.

MVVM is an acronym that’s thrown around frequently in android community and grew a lot of interest after google decided to release it’s Android Architecture Components, with classes built to offer support to this presentation design pattern. Specifically, they actually released an API class called ViewModel. It’s equipped to deal with the lifecycle hell that Google themselves created, not only survive configuration changes, but manage resources so we don’t leak memory in the middle. It includes a pack of so-called “good practices” with it.

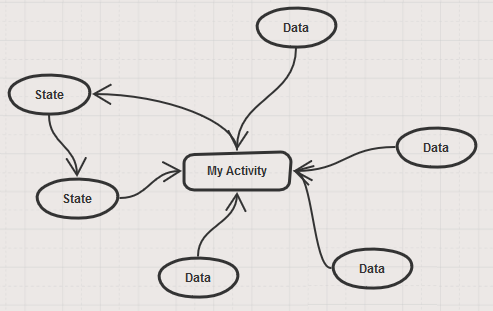

Let’s focus on the green part of the diagram. Theoretically, things should be as easy as declaring our ViewModel class and relying on it to hold our state, while we update it through interactions that we mapped. That is basically what we’ve been doing so far, but with all the instance management.

We can convert our ViewModel to an AAC ViewModel by simply declaring our class as inheriting from it, and things will simply work as they currently are. What is it that we benefit from using this API, after all? Lets reference the docs for once:

A ViewModel is always created in association with a scope (an fragment or an activity) and will be retained as long as the scope is alive. E.g. if it is an Activity, until it is finished. In other words, this means that a ViewModel will not be destroyed if its owner is destroyed for a configuration change (e.g. rotation). The new instance of the owner will just re-connected to the existing ViewModel.

So, it is associated with a scope. If an activity or fragment is still referenced in a task stack, it is alive and therefore so should be the ViewModel, but as soon as it’s cleared, the ViewModel is gone and memory is freed. That’s intended behavior, but how? There has to be some better kind of instance management in place, here. Lets look how the first example of usage goes.

final UserModel viewModel = ViewModelProviders.of(this).get(UserModel.class)

There it is, a provider. The API comes along with an engine of its own to make things work as they should. We could try to use it in our activity, but there’s something to pay closer attention to, here. The class ViewModelProviders is static, and provides a static API. It says providers not provider, and can only generate an instance of a ViewModel if we pass at least an instance of an activity or fragment. Not only that, for some reason the activity has to be a FragmentActivity, which our MainActivity is not. That aside, lets see what this “providers” class does.

public static ViewModelProvider of(@NonNull FragmentActivity activity,

@Nullable Factory factory) {

Application application = checkApplication(activity);

if (factory == null) {

factory = ViewModelProvider.AndroidViewModelFactory.getInstance(application);

}

return new ViewModelProvider(activity.getViewModelStore(), factory);

}

The of function will create a provider. That you could probably figure by the fact that you can request an instance of a ViewModel immediately afterwards. Not only it requires either an activity or a fragment, it also can receive a factory that creates an instance of the intended ViewModel (good if you want to inject dependencies to it). If no factory is supplied, it will fallback to the default AndroidViewModelFactory, that isn’t the basic factory. The basic factory would be ViewModelProvider.NewInstanceFactory that calls the empty constructor, but this provider must be ready to supply instances of another kind of ViewModel, AndroidViewModel, which can have a reference to the application. I advise agains using it, but that’s what it is.

One thing that calls my attention, however, is how the activity is not what matters to the provider, but rather that thing called ViewModelStore. It looks somewhat like what we’ve done for our own generic provider, but interestingly enough, who holds it is not the provider, but the activity. And it’s reasonable since we’re always creating a new throwaway provider to get our ViewModel. But still, how can it be? First thing, let us have a look just at that store.

private final HashMap<String, ViewModel> mMap = new HashMap<>();

final void put(String key, ViewModel viewModel) {

ViewModel oldViewModel = mMap.put(key, viewModel);

if (oldViewModel != null) {

oldViewModel.onCleared();

}

}

final ViewModel get(String key) {

return mMap.get(key);

}

Set<String> keys() {

return new HashSet<>(mMap.keySet());

}

Each store is equipped to deal with multiple ViewModels which are referenced via String. Although the store keeps reference to the keys, it is not something it controls. It is as simple as it can be, really. Other than that it only has a clear method that cascades to calling onCleared() on each of the ViewModels it holds.

@NonNull

@MainThread

public <T extends ViewModel> T get(@NonNull String key, @NonNull Class<T> modelClass) {

ViewModel viewModel = mViewModelStore.get(key);

if (modelClass.isInstance(viewModel)) {

return (T) viewModel;

}

if (mFactory instanceof KeyedFactory) {

viewModel = ((KeyedFactory) (mFactory)).create(key, modelClass);

} else {

viewModel = (mFactory).create(modelClass);

}

mViewModelStore.put(key, viewModel);

return (T) viewModel;

}

As expected, the ViewModelProvider.get() method will check it for an instance before calling the factory. The get method we called calls another get method, that receives the key to the instance that store expects. This key is a combination of internal identifiers and the canonical name of the ViewModel. We could manually set the key to our class if we wanted, that’s why the default includes internal identifiers, to avoid conflicts.

How this store serves us is a good question. Inspecting the owner, that is FragmentActivity, we come across something interesting. Inside it there is a static final class called NonConfigurationInstances, that is a set of instances that an activity can hold that appear to be independent of its configuration state. As one would expect, that’s where we’ll find our ViewModelStore. Each activity has it’s own non-configuration data to be kept through configuration changes. There’s quite a lot of trickery going around here and we could even implement our own logic to keep more stuff if we wanted, but it’s fairly easy to break things if we’re not careful. Basically it retains the data as it would retain a fragment with the retainInstance flag set to true.

This solution seems to be really tied to how activities work. We know we could also be using a fragment here. There’s the one thing that keeps both fragments and activities together here: both of them are also implementations of ViewModelStoreOwner. Scope retention here is much different however. We might even say it is slightly more simple, since there are already mechanisms to keep a fragment alive through configuration change. The difference is that instead of having a set of non-configuration instances, the store is just a regular instance. It’s cleared on onDestroy, unless a configuration change is under course.

So we’ve finally figured the kind of sorcery Google engineers pulled out to make this work. It hasn’t always been like that, but it is what it is now. All we need to do then is supply the ViewModelStore to a ViewModelProvider along with a factory that can build our MainViewModel and we can get rid of our flawed GenericProvider.

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity(R.layout.activity_main) {

private lateinit var viewModel: MainViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

viewModel = ViewModelProvider(viewModelStore, ViewModelProvider.NewInstanceFactory())

.get(MainViewModel::class.java)

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

button.setOnClickListener {

viewModel.inc()

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

}

}

}

We can get rid of the lateinit and use a lazy delegate if we want, but that’s not important. As I said, ViewModelProviders currently isn’t taking other type of activity than FragmentActivity, which is something that they should sort out in the coming versions of the API, probably when ComponentActivity reach a more stable version. I’d also like to see a more generic version that takes a ViewModelStoreOwner, but can’t use AndroidViewModelFactory, so it uses NewInstanceFactory as a fallback instead. It certainly suits very well any code base that doesn’t rely on AndroidViewModel anyway. Lets clean things up a bit by creating an extension for the aforementioned scenario.

fun <T : ViewModel> ViewModelStoreOwner.provideViewModel(

modelClass: Class<T>,

factory: ViewModelProvider.Factory? = null

) = ViewModelProvider(

this.viewModelStore,

factory ?: ViewModelProvider.NewInstanceFactory()

).get(modelClass)

Finally leading up to the last version of MainActivity we will see here

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity(R.layout.activity_main) {

private lateinit var viewModel: MainViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

viewModel = provideViewModel(MainViewModel::class.java)

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

button.setOnClickListener {

viewModel.inc()

textView.text = "${viewModel.count}"

}

}

}

We can still mature things up by better handling the states we own, but that’s gonna be it for noew. We learned what we need in order to make AAC ViewModels do their job, and how google supplied that infrastructure.

Hold on a second!

You might have heard a few things about how AAC ViewModels would do their jobs. Such as them being headless fragments (fragments without a view that would be retained through setRetainInstance(true)). That is not completely wrong. ViewModels are not headless fragments and never were, but there used to be a headless fragment to hold the ViewModelStore for an activity instead of the NonConfigurationInstances class. This change is good, its more resource efficient overall. Henceforth your ViewModels should be lot less impactful to the performance.

Those of you who are working with dependency injection might never have to see these providers or factories. The goal is to make ViewModel instances live within the scope of a screen, and frameworks like Koin provide a mechanism to power that kind of instance availability. Dagger could only see a single factory and have multibinding do the rest of the job. If you’re writing your own framework, that might be something you would want to look into.